So you're thinking about getting an MD during your OMS residency? | Part 3 of 3

Fix the programs or change the laws; we repair things for a living.

Options for repairing the OMS MD

As an OMS educator who sees how much sweat and debt the OMS MD demands, I’m frustrated that it’s so brittle. I’m frustrated that we are the only US-trained physicians whose licensure requires special permission in many parts of the US, or who can lose access to an entire profession simply by moving across the Mississippi River. I’m concerned that, with a few exceptions, applicants to our specialty are unaware of these special considerations.

When it comes to getting the MD or not, I don’t believe increased awareness of these issues will change many minds, but forewarned is forearmed. OMS MD licensure is a complicated problem and maybe we can’t fix it right now, but our future colleagues should be better informed; two years of one’s life is not a triviality. That’s the goal of these three articles — to inform.

If you’ve stuck with me this far, it’s time for us to take what we’ve learned about the OMS MD and look at the main categories of solutions and their required tradeoffs.

Change medical school

Change residency

Make OMS a medical specialty

Change state laws

Option 1: Change medical school

Although it would be helpful if CODA provided more accreditation standards around how medical school is integrated into the OMS MD curriculum (currently, there are none), our problems do not lie with medical school. As long as you graduate from an LCME-accredited medical school, all MDs are equivalent for medical licensure in the USA.

Option 2: Change residency - get more ACGME-time from other programs

This is the “Do more general surgery” option. This has been the go-to strategy for most OMS residency programs that need to enhance their graduates’ medical license-ability. However, two years of general surgery is probably the limit we can expect. When (not if) we need three years of ACGME-time, we’ll need a different strategy.

Also, I hope you now have a better idea of how relying on so much general surgery limits the autonomy and growth of OMS and the time required to train residents to the limits of our modern advanced specialty. There is more to know than ever, and knowing it takes time. There is no shortcut.

Adding more general surgery means we’d have to lengthen the overall duration of OMS MD training. Longer residencies are not necessarily a problem (because we have plenty of OMS to teach you for longer than 30 months), but lengthening residency in order to do more surgery of the kinds we cannot practice (like general surgery) is a futile dead end.

Occasionally people will propose that the general surgery program director could just wave their wand and simply “count OMS months as general surgery months”. General surgery will (and often does) count some months of OMS, but not years of OMS. Such an arrangement is unlikely to pass the scrutiny of any general surgery accreditation process and there’s no incentive for general surgery to make this accommodation or take this risk.

When it comes to licensure, ACGME-time isn’t merely the ‘sum of number of months of off-service rotations’; it is the cumulative time spent in a single, coherent accredited curriculum. In our case, this is the general surgery curriculum. This is why you can’t add up the general surgery and other rotations, plus the five months of Anesthesia to get the sum of months you desire.

Without backing from OMS accreditation standards, curricula that rely on one-off agreements with a general surgery program director are a house of cards that can collapse overnight. We need more robust solutions for medical licensure, supported by laws and standards.

Option 3: Make OMS a medical specialty

Becoming a medical specialty solves a lot of problems but, in an inter-professional field like OMS, would spawn many as well. It will be difficult to succeed with this approach for a variety of reasons.

Although moving a specialty to a different profession is probably unprecedented, there is action on this front. The American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (ABOMS) recently applied to become a member board of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), the leading consortium of medical specialty boards.

Being a member board of ABMS is probably the single most important sign that any particular specialty is a ‘medical specialty’. The ABMS is a conservative (as in not-easily-changed) organization and has strict guidelines for accepting new specialties, accepting only two new specialty boards in more than 50 years (Medical Genetics and Emergency Medicine).

Although this initial ABOMS application was not accepted by ABMS, perhaps ABOMS will make another attempt, as is often required for new members. The inclusion of ABOMS as a member board of ABMS would open a wide set of potential options for the specialty of OMS to address our problems with medical licensure.

It would also create some difficult new problems.

Recall that boards like ABOMS certify the status of practicing individuals, while educational accrediting bodies like ACGME certify the status of training programs. These are very different processes. In order to solve the problem of ACGME-time for medical licensure, ABMS membership alone will not be sufficient. OMS residency programs will also need to create and enforce new accreditation standards consistent with ACGME guidelines, which are generally more complex and demanding than CODA standards (most medical training programs are much larger than OMS programs, with more resources to meet standards).

And while double degree OMS programs may be eager to meet these new standards, we don’t want to lose our CODA compliance, so may need to maintain two sets of standards, one for each of our professions. Also, many double degree programs are sponsored by schools of dentistry, to whom the ACGME is a completely foreign entity that may be difficult to navigate. And last but not least, its questionable whether single degree programs would get an invitation - or have any incentive - to comply with ACGME standards, creating very difficult questions about the future of a professionally-diverse specialty like OMS.

Option 4: Change state laws

Let’s recall that medical licensure is, in the end, a legal permission granted by a US state. But, unlike the list of ABMS members, laws are changed all the time. So if we can’t change our training programs to generate more ACGME-time, our best alternative is to change the statutes that require the ACGME-time in the first place.

The good great news is that this has already been successfully achieved in the biggest state in the USA, California. The bad news is that we only have 49 more to go. Let’s hope the old adage, ‘As goes California, so goes the nation’ holds true here.

California OMS created a model for the rest of the USA.

A few years ago, the Medical Board of California announced a plan to increase their minimum ACGME-time for medical licensure from one year to three years (this plan is now law). The state’s OMS MD training programs recognized the existential threat posed by this new statute so, working alongside CALOMS (California’s OMS professional org), the OMS educators and surgeons of California successfully lobbied their lawmakers for an OMS-specific carve-out that maintains a pathway to medical licensure for the OMS MD in a three-year ACGME state.

So now, in California, both CODA and ACGME-accredited time is recognized when qualifying for medical licensure, and licensure is granted with a combination of :

MD from a U.S./Canadian medical school

24 months of CODA accredited OMS residency training subsequent to the MD

12 months of approved postgraduate medical training — either ACGME-time or RCPSC or CFPC (Canadian medical training) time.

This solution is exceptional because it acknowledges CODA-time - proving that such a thing is legally possible for medical licensure - and it creates a precedent for other state medical boards to follow. It’s legal, durable, and doesn’t rely on the interpretation of random program directors.

However, the special qualities of the California model are hyper-local. If the OMS wants to work in any other state, they’ll face all the previously discussed obstacles. For this model to really transform the landscape for the OMS MD, many more states will have to adopt something similar.

Of all the options, I’m the most optimistic about this one because it has proven feasibility and it keeps the specialty intact, preventing OMS MDs from needing to find more radical workarounds to maintain medical licensure pathways. The strength of OMS, like any professional group, is in our numbers.

For all the other states with OMS MD programs, any future proposal to increase licensure to three years of ACGME-time would trigger the need to work with their own state lawmakers to build a pathway to OMS MD licensure — or face loss of the MD.

I think most state lawmakers have an incentive to create these special pathways because politicians want more providers caring for citizens. With our excellent training, OMS MDs have no quality concerns and, because it demands CODA-time, such laws won’t create a back door for other fields to exploit.

Conclusions

When it comes to the OMS MD and medical licensure, one way or another we are at a crossroads, and choosing to do nothing is still choosing to do something.

Yes, those with an OMS MD are mostly OK right now, but I’m not concerned about today; I’m concerned about our future colleagues who are just starting out. A don’t-worry-be-happy-it’s-always-worked-out-before attitude will continue to work for a while but, without action, the OMS MD will almost certainly lack the ability to satisfy medical licensure in some not-too-far-off decade. I’ve done my best to explain why I think the OMS MD is in peril, and if I am wrong, I encourage you offer a different explanation in the comments.

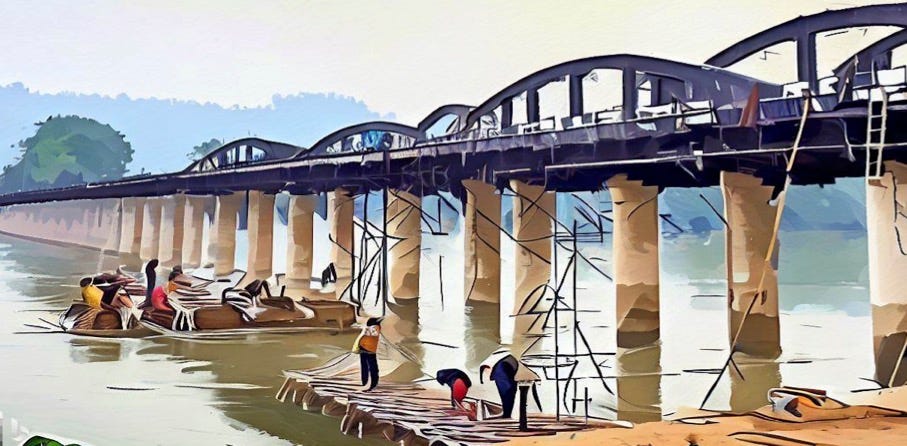

There are no easy solutions here. At a national level, there is no collaboration between ACGME and CODA, the professions of Dentistry and Medicine are mutually disjoint siloes, and those with the OMS MD are stranded on the bridge between them.

To Dentistry at large, the trials and tribulations of OMS MDs are the niche problems of a fringe group. We - those with an OMS MD - are on our own; no one is coming to our aid. We can rely on our single degree colleagues to help us as far as they are able but we are the architects and inhabitants of this quirky edifice.

The OMS MD is a valuable invention; we, and we alone, have any incentive to repair it.